The Mission Briefing

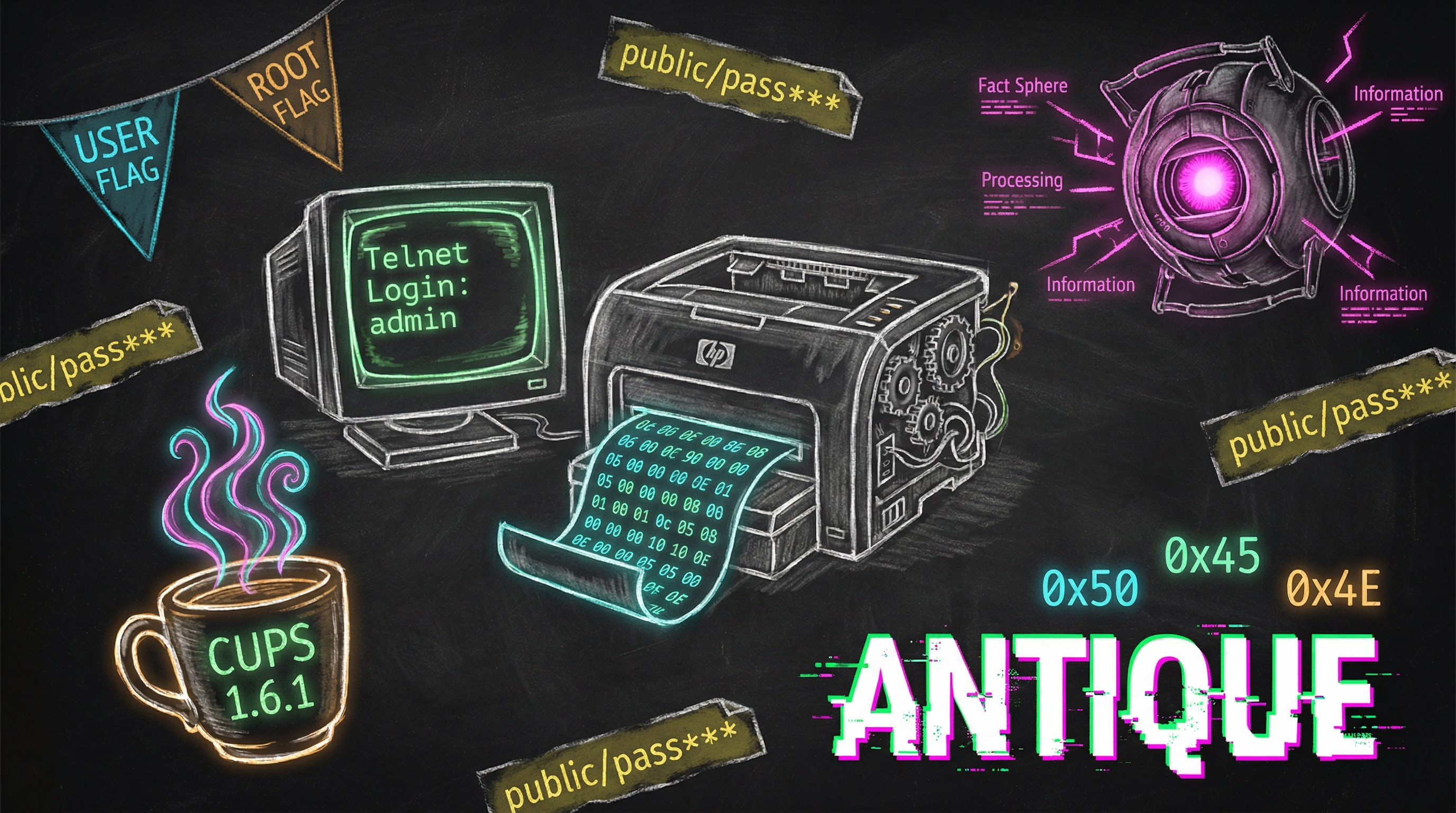

The box was called Antique. A name that turned out to be painfully accurate.

My initial TCP scan came back with almost nothing — just port 23. Telnet. In 2026. I stared at the terminal for a moment, processing the fact that somewhere in the world, a machine was still running a Telnet service like it was 1995.

I connected and was greeted by an HP JetDirect banner. A printer management interface. The kind of device that network admins deploy once, configure never, and forget forever.

It wanted a password. I didn't have one. Yet.

Reconnaissance

TCP wasn't telling me much, so I shifted to UDP. This is something I'm learning to do more often — a lot of beginners (myself included) skip UDP scans because they're slow. But UDP services can be goldmines.

Port 161. SNMP — Simple Network Management Protocol. The protocol that lets you query network devices for their configuration data. The key word here is "simple," because the security model for SNMPv1 is basically a shared password called a "community string." And the default community string is...

Here's the thing about SNMP that made this box click for me: network devices store their configuration in a tree structure called a MIB (Management Information Base). Every piece of data has an address called an OID. You can walk the entire tree and dump everything the device is willing to share. With the default public community string, that's usually... everything.

The Password in the Printer

I ran an SNMP walk against the target:

Buried in the output was a specific OID from HP's enterprise MIB space:

Hex-encoded ASCII. I decoded it and got:

The Telnet password for HP JetDirect. Stored in the SNMP MIB tree. Readable by anyone who tries the default community string. This is what "defense in depth" looks like when there's no depth.

Initial Foothold

I logged into the JetDirect Telnet service with the extracted password. Inside, I discovered the exec command — it lets you run system commands directly from the printer management shell.

I was in as the lp user — the printer service account. More importantly, I was in the lpadmin group. That detail would matter later. A lot.

User Flag

The user flag was right there in lp's home directory:

One down. But getting from a printer service account to root? That's where the real lesson was hiding.

The Privilege Escalation

I started enumerating from the inside. One of the most valuable things to check after getting a foothold is what's listening on localhost — services bound to 127.0.0.1 that you'd never see from an external port scan.

Port 631. CUPS — the Common Unix Printing System. Running on localhost only, invisible from the outside. I checked the version:

CUPS 1.6.1. This version has a known vulnerability: CVE-2012-5519.

Here's how it works, and this is the part that really taught me something: CUPS has a configuration directive called ErrorLog that specifies where error logs are written. Members of the lpadmin group can change this setting using cupsctl. The trick is that CUPS runs as root, so when you point the error log at an arbitrary file, CUPS reads it with root privileges and serves the content through its web interface.

It's a local file read vulnerability, but it only works if you're in the lpadmin group. Which I was.

The exploit was two commands:

Set the error log to /root/root.txt. Then read the "error log" through CUPS' web interface. Root flag captured.

What I Learned

This box taught me more about overlooked attack surfaces than any other I've done so far:

- Always scan UDP — SNMP on port 161 was the entire foothold. A TCP-only scan would have left me staring at a password prompt forever

- Default SNMP community strings are everywhere —

publicandprivateare the admin/admin of the network device world. Always try them - Printers are computers too — HP JetDirect, CUPS, print spoolers — these are full services with real vulnerabilities, not just things that jam paper

- Check localhost services after getting a foothold —

ss -tlnpreveals services bound to 127.0.0.1 that external scans can never see. These are often your escalation path - Group memberships matter — Being in

lpadminlooked irrelevant until I found CUPS. Always checkidand research what each group can do - Old CVEs are still live — CVE-2012-5519 is from 2012. Fourteen years old and still providing root access