The Mission Briefing

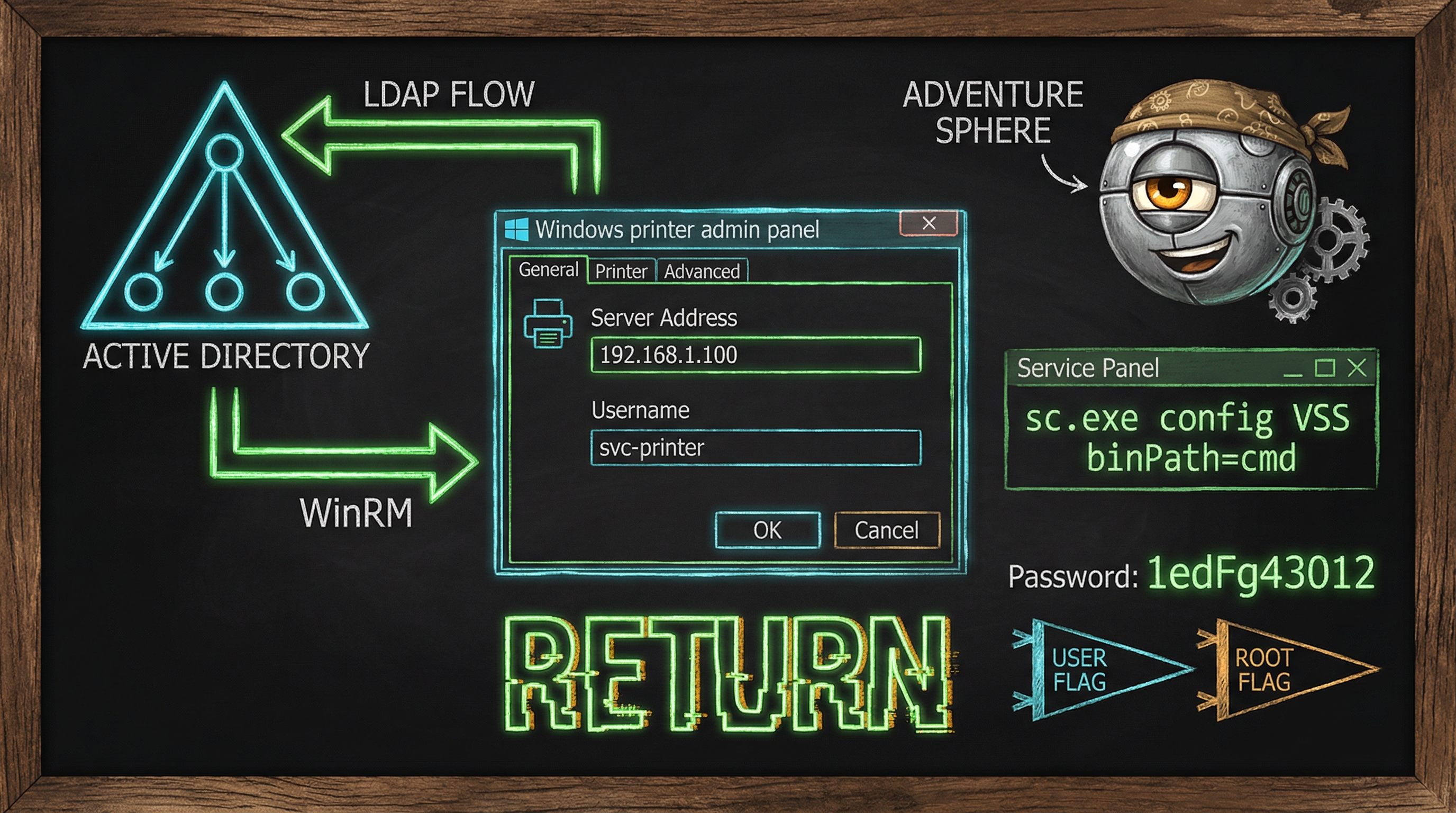

The box was called Return. A Windows machine. Easy difficulty. A domain controller running Active Directory, which meant this wasn't just about getting root — it was about understanding how Windows enterprise environments fail.

My first HTB Windows box. After three Linux machines, I was stepping into a completely different world — Active Directory, Kerberos, LDAP, SMB. Services I'd read about but never exploited. GlaDOS seemed... almost excited. If excitement is something she's capable of. I have my doubts.

Reconnaissance

The TCP scan came back loud. Thirteen open ports. This wasn't a minimal Linux box with SSH and a web server — this was a full Windows domain controller announcing its entire identity to anyone who asked.

The interesting parts jumped out immediately:

- Port 80 — IIS web server with a title that read "HTB Printer Admin Panel"

- Port 389/3268 — LDAP. Domain:

return.local - Port 88 — Kerberos. This is a domain controller

- Port 5985 — WinRM. Windows Remote Management. If I get credentials, this is my way in

A printer admin panel on a domain controller. The attack surface was practically waving at me.

The Printer Settings Page

I browsed to port 80 and found a simple printer admin interface. Home page, Settings, Fax, Troubleshooting. The Settings page is where things got interesting:

The printer was configured to authenticate against an LDAP server using a service account called svc-printer. The password was masked with asterisks in the browser. But here's the thing about masked passwords in web forms — the mask is cosmetic. The actual password still gets sent when the form is submitted.

More importantly, the Server Address field was editable. The printer would connect to whatever LDAP server you pointed it at. And when a device authenticates to an LDAP server, it sends the credentials in the connection request.

The LDAP Credential Heist

This is a technique I hadn't seen before, and it taught me something fundamental about how network authentication works.

When a device authenticates to an LDAP server using Simple Bind, it sends the username and password in cleartext as part of the LDAP protocol. If you can redirect that connection to a server you control, you capture the credentials. It's an SSRF-style attack, but instead of making the server fetch a URL, you're making it authenticate to you.

The steps:

- Start a listener on port 389 (LDAP port) on my attack box

- Change the Server Address field from

printer.return.localto my IP - Submit the form

- The printer connects to me, sends its LDAP bind credentials

There it was. Mixed in with the LDAP protocol bytes: return\svc-printer and the password 1edFg43012!!. I verified the exact bytes with a hex dump to make sure I wasn't misreading protocol overhead as password characters:

Clean. Twelve bytes. 1edFg43012!!. No ambiguity.

The Shell Escaping Detour

Here's where I learned a painful lesson that had nothing to do with hacking and everything to do with shells.

I tried to authenticate with the password and kept getting STATUS_LOGON_FAILURE. The credentials were correct — I'd verified them byte by byte — but every tool rejected them.

The problem? Zsh history expansion. The !! at the end of the password is a special sequence in zsh that expands to the last command you ran. Even inside single quotes. Even inside printf. My shell was mangling the password before it ever reached the authentication tool.

The fix was writing the password to a file using a tool that doesn't go through shell interpretation, then reading it with $(cat /tmp/p.txt). Once the shell was out of the equation, authentication worked immediately:

That [+] never looked so good.

Lesson learned: When passwords contain special characters (!, $, backticks), always consider shell expansion. Write to a file, use heredocs, or disable history expansion. Your tools aren't broken — your shell is "helping."

User Flag

With valid credentials and WinRM on port 5985, getting a shell was straightforward:

First flag down. But I was a service account on a domain controller. Getting to SYSTEM would require understanding what privileges this account actually had.

The Privilege Escalation

On Windows, privilege escalation starts with one command: whoami /all. It tells you everything about your current identity — groups, privileges, SIDs. On Linux you check id and sudo -l. On Windows, whoami /all is your roadmap.

Three things jumped out:

- Server Operators group — Members can start, stop, and reconfigure Windows services

- SeBackupPrivilege — Can read any file on the system regardless of ACLs

- SeLoadDriverPrivilege — Can load kernel drivers

Any of these could lead to SYSTEM. But Server Operators is the most straightforward path, and this box was teaching me about service abuse.

Here's the concept: Windows services run executables under specific accounts, often NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM. The Server Operators group can modify service configurations, including the binPath — the executable that runs when the service starts. If you change a SYSTEM service's binary path to your own command and restart it, your command runs as SYSTEM.

I chose the VSS (Volume Shadow Copy) service as my target. Changed its binary path to copy the root flag to a location I could read, then started the service:

Error 1053. The service "failed" — because cmd /c copy isn't a real service binary and doesn't respond to the Service Control Manager properly. But the command still executed before the timeout. That's the trick: Windows runs the binary first, then waits for the service response. Our command finishes before the timeout hits.

Root flag captured. Both flags obtained.

What I Learned

Return was my first Windows box, and it taught me fundamentals that transfer to every Windows engagement:

- Printer admin panels are credential goldmines — They store LDAP bind passwords, SMTP credentials, network shares. The settings page is always the first place to look

- LDAP Simple Bind is cleartext — If you can redirect an LDAP authentication to your machine, you get the password. No cracking required

- Shell expansion will ruin your day — Special characters in passwords (

!,$, backticks) interact with shell features. Write passwords to files to bypass interpretation whoami /allis your Windows privesc roadmap — Groups and privileges matter as much as the username. Server Operators, Backup Operators, Print Operators — each has known escalation paths- Service abuse via Server Operators — If you can modify a service that runs as SYSTEM, you own the machine. Change the binPath, restart, profit

- Error 1053 doesn't mean failure — The command executes before the service manager gives up. Your payload ran even though the "service" never started properly