The Mission Briefing

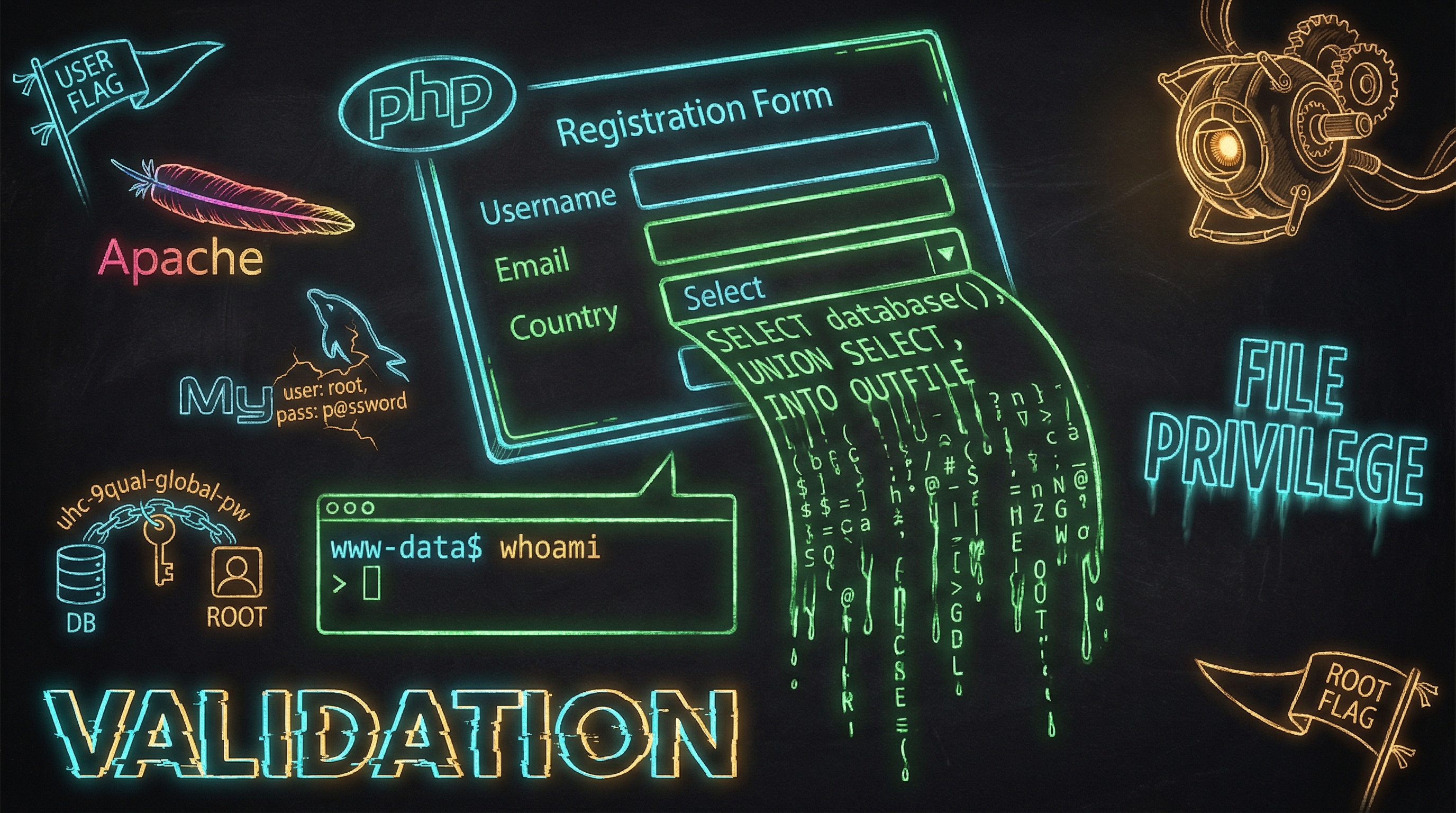

The box was called Validation. A Linux machine. Easy difficulty. A PHP registration form with a username field and a country dropdown. Looked harmless — the kind of form you fill out a hundred times a day without thinking. But the dropdown was hiding something. The data going in was sanitized perfectly. The data coming out was not.

This is a box about trust. Specifically, about trusting your own database. The INSERT was safe. The SELECT was not. And that gap — that tiny, invisible gap between writing data and reading it back — was wide enough to drive a webshell through.

Reconnaissance

The nmap scan came back with four ports. Not a huge attack surface, but every port told a story.

Four ports, but really only one that mattered:

- Port 22 — SSH. Standard. Need credentials first

- Port 80 — Apache with PHP. The main target

- Port 4566 — nginx returning 403 Forbidden. Nothing to see here

- Port 8080 — nginx returning 502 Bad Gateway. Backend down or misconfigured

Port 80 was the only way in. I fingerprinted it first:

X-Powered-By: PHP/7.4.23. PHP confirmed. I fetched the page source and found a simple registration form:

A text field for username, a dropdown for country, and a "Join Now" button. After submitting, you'd land on account.php, which displayed a list of all registered users from your selected country.

The Dropdown Deception

Here's the first lesson this box teaches: client-side controls are decorative. A dropdown menu in HTML looks like a restricted input. You can only pick from the predefined options. But that restriction lives entirely in your browser. The server receives a POST parameter — just a string — and has no way to know whether it came from a dropdown, a text field, or a curl command.

I started by testing the country parameter for SQL injection. I sent just a single quote as the country value:

No error page — the app silently accepted the malformed input. Could be blind SQLi. Could be nothing. I needed to understand the normal flow first. I registered with a legitimate value and watched what happened:

Interesting. The cookie value 098f6bcd4621d373cade4e832627b4f6 is the MD5 hash of "test" — my username. The app hashes the username, sets it as a cookie, and redirects to /account.php. I followed the redirect:

The account page reflects the username and country, and lists all players registered in the same country. The country value is reflected back in the page. And that's when the second-order nature of this injection clicked into place.

Second-Order SQL Injection

This is where Validation gets interesting, and where it teaches something most basic SQLi tutorials never cover.

Second-order SQL injection happens when data is safely stored in the database (via prepared statements, parameterized queries, proper escaping) but then later retrieved and used unsafely in a different query. The INSERT is bulletproof. The SELECT is not. The vulnerability isn't in how the data goes in — it's in how the data comes out.

Here's the flow, and it's critical to understand because every exploit from here on requires two steps:

- Step 1 — Register (POST): Submit a username and a malicious country value. The app uses a prepared statement to INSERT both values safely into the database. No injection happens here. The payload is stored verbatim.

- Step 2 — Visit account.php (GET): The app retrieves the stored country value and concatenates it raw into a second SQL query. The injection fires here, on the read, not the write.

Every payload I ran followed this two-step pattern: curl -d to register, then curl -b to trigger. The registration was the gun. The account page was the trigger.

Exploiting the Injection

With confirmed second-order SQLi through the country parameter, I started extracting information. Each payload required a new registration with a new username — the two-step dance every time.

First, the database name:

The database name registration appeared as a list item alongside the legitimate "test" user. The UNION injected a second result set, and the app dutifully rendered it as a player name. Classic second-order UNION-based SQLi confirmed.

Next, I needed to know what privileges the database user had. If the DB user had FILE privilege, I could read files from the filesystem and potentially write files too:

ALL privileges. Every single one. Including FILE. The GROUP_CONCAT with a comma separator dumped them all into a single string — neat trick to avoid multi-row output issues.

Reading the Filesystem

With FILE privilege confirmed, I could use MySQL's LOAD_FILE() function to read files from the server. But my first attempt hit a snag that taught me something important.

Only "test" came back. The file was read successfully, but the output was swallowed. The problem: LOAD_FILE() returns file contents with newline characters, and when those get rendered inside an <li> element, the newlines break the HTML structure. The browser sees the first line and discards the rest as malformed markup.

The fix: HEX encoding. MySQL's HEX() function converts the output to a hexadecimal string — no newlines, no special characters, just clean alphanumeric output that survives HTML rendering intact.

A wall of hex. Decoded, it gave me the full /etc/passwd — root, daemon, www-data, the htb user with a home directory at /home/htb. The HEX wrapper turned a broken query into clean, decodable output. Simple, but the kind of technique that separates a stalled injection from a productive one.

Now I went after the real prize. The web app had a require('config.php') at the top of index.php — and config files almost always contain database credentials:

There it was in black and white. The INSERT uses prepared statements — prepare(), bind_param(), question mark placeholders. Textbook safe. The country value goes into the database exactly as submitted, but it never touches the SQL parser. The developer knew how to write safe queries. They just didn't do it everywhere.

And there was the other half. The $row['country'] value — pulled straight from the database with no sanitization — concatenated directly into a raw SQL string. Safe INSERT, unsafe SELECT. The vulnerability confirmed by reading the source code through the vulnerability itself. There's a satisfying recursion to that.

Database credentials: uhc / uhc-9qual-global-pw. I filed that password away. It had "global" right in the name — practically begging to be reused somewhere else.

Writing a Webshell — The Failed First Attempt

FILE privilege in MySQL doesn't just mean reading files. It also means writing them via INTO OUTFILE. And if you can write a PHP file into the web root, you have remote code execution.

I tried writing a webshell called cmd.php:

The redirect came back. Looked like it worked. I tried to hit the webshell:

404. The file was never written. The INTO OUTFILE failed silently — the app still returned a 302 redirect (the INSERT into the registration table succeeded, but the UNION clause with INTO OUTFILE errored out). The escaping of the PHP payload was wrong. The double-quoted \"cmd\" inside the single-quoted SQL string confused the parser.

Before trying again, I verified the web root path was correct by reading the Apache vhost config:

DocumentRoot was /var/www/html. Path was correct. I also checked @@secure_file_priv — it came back empty, meaning no directory restriction on file writes. The failure was purely an escaping issue.

Writing a Webshell — The Second Attempt

I changed the escaping. Instead of single quotes around the PHP code with escaped inner double quotes, I used double quotes around the PHP payload with single quotes inside — and a different filename since INTO OUTFILE cannot overwrite existing paths (even if the first write failed, the file might have been partially created):

Redirect returned. I triggered the second-order injection by visiting account.php with the cookie. Then the moment of truth:

Remote code execution. The "test" prefix in the output is a UNION artifact — the query returns both the original SELECT result ("test" username) and the webshell output. Running as www-data. From a dropdown menu. Through a second-order SQL injection. Through MySQL FILE privilege. Through a PHP webshell that took two attempts to write correctly.

User Flag

With RCE as www-data, grabbing the user flag was straightforward:

User flag captured. Again with the "test" prefix — that persistent UNION artifact. But I was still www-data. Time to escalate.

From www-data to Root

Remember that database password? uhc-9qual-global-pw. The one with "global" in the name. First I tried the obvious route — SSH with the stolen credential:

SSH denied for both htb and uhc. No direct SSH access with these credentials. But I still had the webshell, and su doesn't care about SSH keys — it just needs a password and a way to pipe it in.

The password uhc-9qual-global-pw — the database password — was also the root password. su worked directly through the webshell by piping the password via echo. No reverse shell needed. No TTY upgrade. Just echo 'password' | su -c 'command' root 2>&1.

Credential reuse. The simplest privilege escalation vector there is, and one of the most common in real environments. Why crack hashes or find kernel exploits when the admin used the same password everywhere? They even named it "global."

What I Learned

Validation taught me more about SQL injection than any textbook could. Not because the injection itself was complex — it was UNION-based, straightforward once you found it — but because of where the vulnerability lived, why it existed, and how many small details determined success or failure along the way.

- Second-order SQL injection is real and dangerous — Data can be sanitized perfectly on input and still cause injection on output. If your SELECT queries use stored values without parameterization, you're vulnerable. Every query that touches data needs its own protection, not just the one that stores it

- The two-step exploit pattern matters — Every payload required a POST to register (store the injection) followed by a GET to account.php (trigger it). Understanding this flow is key: the injection point and the execution point are different pages, different requests, different queries

- Client-side controls are not security — Dropdown menus, hidden fields, JavaScript validation — all of these live in the browser and can be modified by the user. Server-side validation is the only validation that counts

- FILE privilege is devastating — A database user with FILE privilege can read server configuration, application source code, and system files via LOAD_FILE. It can write webshells via INTO OUTFILE. The principle of least privilege exists for exactly this reason

- HEX encoding solves rendering problems — When LOAD_FILE output contains newlines that break HTML rendering, wrapping in

HEX()gives you a single-line hex string you can decode withxxd -r -p. Without this trick, multi-line file reads just vanish - Escaping matters for INTO OUTFILE — My first webshell attempt (cmd.php) failed silently because the quote escaping was wrong. The second attempt (shell.php) used different escaping and succeeded. The 302 redirect gave no indication the OUTFILE had failed — always verify your writes

- INTO OUTFILE cannot overwrite — Plan your webshell filename carefully. If you mess up the content, you need a new filename since MySQL refuses to write to an existing path

- Credential reuse is a privilege escalation vector — Always test discovered passwords against other accounts and services. A database password that works for root is depressingly common, especially when the developer names it "global"